A decade at the helm of the World Energy Council (WEC)Published on December 20, 2019

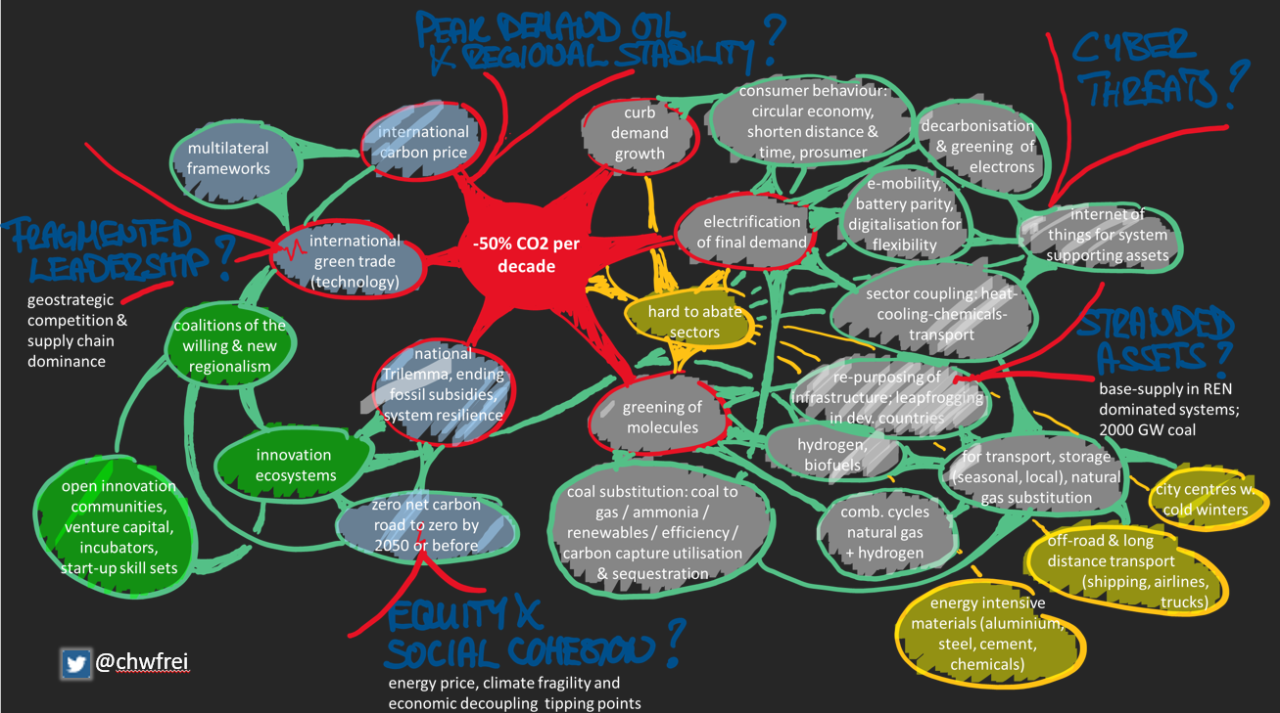

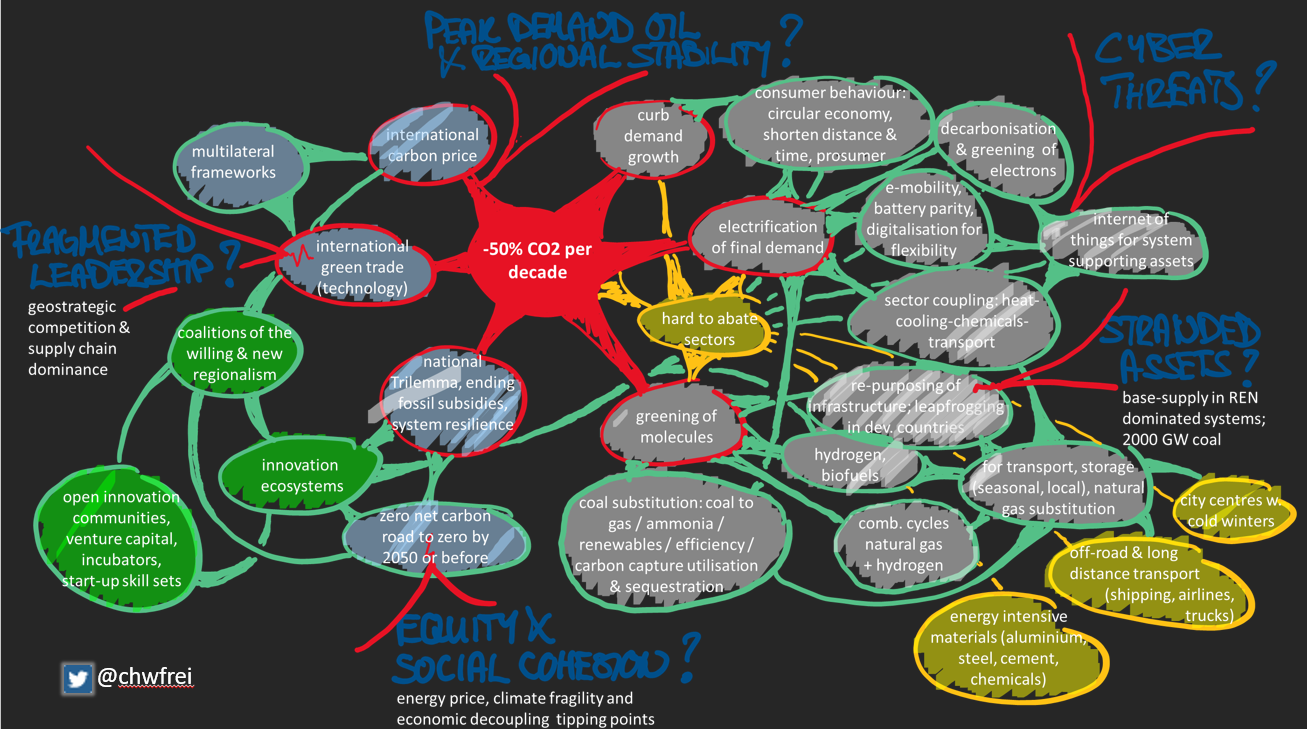

Energy transformation & decarbonisation map

Christoph W. Frei

Partner at Emerald Technology Ventures - Adjunct Professor, EPFL - Board, Energy Web Foundation - former member of UN Secretary General’s Advisory Board on Sustainable Energy

6 articles Follow

With the conclusion of my 10 years as CEO of the World Energy Council I have received many encouragements to share a perspective on what a very special decade at the helm of this wonderful organisation has taught me. These have been incredibly enriching, insightful, and gratifying years. I am richer in understanding energy and sustainability challenges and solutions, in learning about managing a stellar team in a multi-cultural environment, and from meeting with many very special and committed people around the world.

Perhaps most importantly, the role leaves me with a strong sense of urgency. We need dramatically more ambition and acceleration in the energy transition space and moving forward I will invest my full professional energy to this ambition.

Thank you for all your support to the Council over the past decade and also to these who have provided smart comments and additional thoughts to an earlier version of this perspective.

Looking back at the Council’s founding history

100 years ago, at the time of the foundation of the World Energy Council, in a context of fragile post-WWI peace in 1918, the major concern was to get the economy back on track and prevent the next war. Peace was followed by calls for a new international order in which global organisations would steer and regulate potentially sensitive areas of international life and trade.

Back then, ‘new internationalists’ offered the diagnosis that economic globalisation in the nineteenth century had outpaced national politics. Political institutions now needed to catch up and create new bodies that could see and act above those of nation states.

Energy was among the most explosive subjects in international relations, and the first World Power Conference in 1924, debating current and emerging energy issues, was a major experiment and manifestation of the search for a new international order after the upheaval of the First World War. The Prince of Wales expressed this in his opening speech and commended the Conference as a significant step towards removing ‘one of the greatest obstacles to progress’ arising from the disparity in the utilisation of knowledge.

Emerging technology in a different area, the development of short-wave radio, would bring about ‘the unity of world thought and opinion’. Lord Reith, managing director of the recently formed British Broadcasting Corporation expressed this at one of the WPC panels, pointing out that ‘the wireless ‘ignores the natural barriers which estrange mankind.’

The World Power Conference was after the same goal as the radio: both were seeking to create a ‘unity of world thought’ through a meeting of minds on all matters relating to energy and its application. Many hoped WPC would be a technological ‘League of Nations’, a term used by many including, at the opening of the WPC conference in Berlin in 1930, the German President, Paul von Hindenburg.

The main inspiration behind the World Power Conference was Daniel Nicol Dunlop whose principle objective was to create an international organisation that could stand above politics. Born in 1868 in Kilmarnock, Scotland, Dunlop was a visionary central in the formation of the British electrical industry.

Dunlop had originally wanted to fund a World Economic Conference. However, he reasoned against it and confessed to a friend: ‘I could see clearly that it was impossible to bring together politicians, and as all the important economic decisions are in the hands of politicians, it was hopeless to fund an international economic body as a first step. But it was possible to bring together human beings in the field of technical questions, and so I started there.

This was the context 100 years ago.

Energy in transition, before and now

Almost 100 years after the creation of the World Energy Council, in September 2018, UN Secretary General António Guterres has referred to climate change as the defining issue of our time and made it clear that we are at a defining moment. A year later, while the young activist Greta Thunberg stands as symbol for a wave of young global climate movements, the conference of parties COP25 in Madrid is incapable to marking any progress.

The societal tension on climate and energy issues is at a tipping point in many countries around the world. The way we produce and use energy is a large part of the cause of today’s climate problem and must be the source for tomorrow’s solution to this extraordinary challenge. Energy represents 80% of carbon emissions, the power sector about half of this and coal alone 30% of total emissions. In our quest for solutions it is important to understand relevant past developments and underlying drivers, as well as current issues, innovation and policy trends and draw relevant lessens.

Let’s consider what have been the most defining events shaping energy over the past century, look at critical drivers and try and understand where we stand with these drivers today.

Over a period of the last 100 years, the most significant achievement in the energy space was clearly the establishing of previously non-existent energy supply chains, infrastructure and systems to the benefit of 6 billion people, locking in about half of the worlds invested capital and enabling economic development. The most important underlying inventions go further back and include James Watt’s steam engine (1776) and Thomas Edison’s light bulb (1879).

Arguably, over a period of the last 50 years the most significant event was the 1973/79 oil shock and the formation of OPEC, ending non-cartelised low-cost oil and giving birth to the first international push for energy efficiency, unleashing research on renewables and battery technology including this year’s chemistry Nobel Prize awarded work by Stanley Whittingham, contributing to developing lithium-ion batteries.

If we consider the period of the last 20 years the most cited event has been the shale revolution, leading to US energy independence, undermining the cartel and, ending fears of peak supply.

We note that so far this seems largely a history of oil & coal (with some thinner chapters on hydro and nuclear). This is about to change.

Over the last 10 years the most significant event was certainly the Fukushima disaster, leading to policy reactions that enabled the exponential solar photovoltaic explosion and demonstrating the real possibility of a greening of supply with new renewables.

Over the last 5 years, driven by COP21 in Paris in 2015, we could observe a mindset shift accepting the plausibility if not necessity of peak oil demand. Increasing climate pressure, the peaking of per-capita primary energy demand within reach and an accelerating electrification of final demand have made this issue an accepted topic in board rooms and ministries of most relevant resource players.

These past developments have largely been driven by a mixture of ground-breaking innovation, geostrategic competition, and societal response to disruptive events, where determined entrepreneurship and unleashed capital markets secured maximum value from precious primary resources.

Where are we today with these drivers?

Climate change is humanity’s number one challenge and cause for a growing number of catastrophic and disruptive weather events. This makes decarbonisation the central force among a wider set of drivers behind a deep energy transition. Disruptive climate events ranging from hurricanes over draughts, aggravated El Nino to extreme fires start triggering social response pressure and action in affected territories.

The pressure to innovate is increasing and the focus is shifting away from owning resources to capturing value closer to customers through platforms and demand side aggregators, where margins increase thanks to the enhanced availability of data and information, which enable new service opportunities. Meanwhile, the cost decrease on the renewables side continues and solar PV front-running projects are contracted below 1.5 c/kWh, equipped with storage for 24/7 energy delivery below 8 c/kWh.

Fig.1 – Energy transformation & decarbonisation map. Areas that need to be promoted and accelerated to achieve required carbon emission targets as well as main risks.

China and India are moving to aggressive e-mobility schemes (depending on a 90% Chinese controlled battery supply chain). And, on the digital frontier start-ups develop business models driving value from decentralised assets with system benefits, using uberisation concepts, big data, internet of things and artificial intelligence, and we have also seen the first listing of an energy focused blockchain, supported by major energy players.

Further, electrification of demand is probably the widest referred-to trend. Today, electricity represents about 20% of final demand. At a time when for the first time we have less than one billion people without access to energy thanks to new and rapidly spreading decentral electrification solutions, the electrification of demand is accelerating through e-mobility, heat-pumps, and electrification of industrial processes. Doubling electricity in 20 years at a time where energy demand is still growing is expected to bring the electricity share to about 30% of final demand.

But electrification has limitations, particularly in hard-to-abate sectors such as long-distance and off-road logistics (shipping, airlines, trucks), high-density urban centres with cold winters or hot summers or, energy intensive materials (cement, aluminium, steel, chemicals). With an increase from 20% to 30% electrified final demand by 2040 we still depend on 70% energy supply from molecules. Hence, molecules need radical greening as per Japan’s call at this years’ G20, if we are serious about climate change mitigation.

One difficult challenge is the 2’000 GW of installed coal power capacity that represent roughly a third of global CO2 emissions. 90% of these plants are in Asia and their average age is about 10 years, which means they may well be operated for another 40-50 years. Retrofitting these to natural gas (or wood) will be possible in some cases where relevant resources are available, which is not the case e.g. in India. Carbon capture utilisation or sequestration retrofitting is a hard path as it requires a significant capital injection and a multi-month retrofit with unproductive down-time for the plant.

A Japanese pilot to retrofit a coal plant to ammonia explores an alternative pathway of a stepwise greening with minimal disruption and capital requirement by building on existing supply chains and infrastructure. Ammonia is the biggest traded chemical and could be sourced, initially from traditional “grey” (fossil based) production, with the objective to substitute these by increasing shares of “blue” (with carbon capture and sequestration) and green (e.g. from green power-to-X) ammonia input. Countries with existing ammonia production infrastructure and CCS or renewable power-to-X potential would be best placed to stepwise green their existing ammonia production. The key difference of such a “green molecules vision” compared to the boom-and-bust hydrogen economy hype in the early 2000s is that this time it is all about unlocking pathways that re-purpose and re-use existing rather than build new infrastructure.

Tense geopolitics define a tougher environment for multilateral progress on trade or climate agendas. International climate change mitigation efforts have slowed since Paris COP21 in 2015 while mounting trade barriers slow down green technology deployment with WTO paralysed by the US veto on the election of judges for dispute resolution. The Council’s Hard Rock scenario that describes a world of fragmented leadership was seen as least plausible in 2016 and is now seen as most reflective of current realities. This dramatic erosion of trust in multilateral progress happened over a period of only three years.

In summary, the main drivers today are in the areas of decarbonisation, digitisation, decentralisation, electrification, greening of molecules. For the transition to be cost effective it needs to be realised through re-purposing and re-using of existing rather than building of new infrastructure. The key question is how we can accelerate progress in a context where multilateral processes are paralysed.

Lots of similarities – important differences

What did we say was the context 100 years ago? A context defined by a major unifying challenge; by a call for a new international order; with energy as a hot topic; with technology and communications revolution as an enabler; and with the creation of a technical league to advance practical solutions.

In many ways, this sounds very familiar, looking at today’s context – yet there are very important differences:

As we did 100 years ago, we debate again the need of a new international order. The diagnosis is again that economic (capitalist) globalisation has outpaced national politics, no longer “rises all boats with the tide”, suffers from multinationals tax evasion, borderless platform monopolies or, WTO compliant carbon leakage. For many of these issues, eyes move to Asia and to the question whether China will step up as a good and caring global citizen.

In 1918 the uniting purpose was to get the economy back on track and prevent the next war, and the response was an inclusive League of Nations. Today, humanity’s greatest challenge is climate change at a moment when existing multilateral organisations fall short of expectations or are paralysed, when fragmented leadership is the biggest threat to progress. As a result, there is increasing acceptance and support for exclusive coalitions of the willing of state and non-state actors as critical part of the solution. Regional alliances are formed or are revived to defend geostrategic interests.

We have moved beyond short-wave radio, but new frontiers of communication are again seen as a game-changing opportunity. This time it is not to overcome natural barriers which estrange mankind but to overcome technical boundaries which separate things: The ‘internet of things’ in energy will connect a rapidly growing number of devices – fridges, car batteries, heat pumps, cooling centres – and thereby enable system flexibility allowing for increasing shares of intermittent renewables.

100 years ago, the response was to create an inclusive technical league of nations. Today, the key to unlock innovation acceleration is through building and strengthening innovation ecosystems and platform economics, coalitions of the willing and regional partnerships, with the objective to nurturing talent, delivering relevant capital vehicles, and agile regulatory frameworks.

The change we need

Learning from the before and now we can summarise the following guiding principles to help guide the way forward and successfully manage the energy transformation and decarbonisation:

1. Rather than believing in an all-electric vision, an honest attempt to fight climate change must include both green electrons and green molecules. Digitisation and decentralisation are the other important driving forces that in many ways support the overall transition.

2. Rather than building new infrastructure in many places the solution must be about greening and re-using existing supply chains and infrastructure and thereby unlocking low-cost transition pathways.

3. Rather than trusting in markets alone the solution must be to advance these issues through well-defined objectives and supporting frameworks such as net zero carbon. Effective national and international deployment of best green goods and services are critical and will be hampered by trade wars.

4. The current geopolitical context doesn’t support momentum from multilateral organisations and there is no alternative to these organisations in delivering a global carbon price or prevent trade barriers on green goods and services. However, to accelerate we need effective coalitions of the willing and regional alliances consisting of state and non-state actors, which deliver innovation ecosystems and ambitious transformative break through projects.

5. All this does is not feasible with dramatic societal change. We must embrace the change towards a more local, considerate, re-using, recycling, circular economy.

With these principles in mind, we need a number of critical milestones to enable carbon emission reduction objectives:

- In the next 5 years: achieving 15% e-vehicle sales in major markets, supported by the necessary charging infrastructure developments, while at the same time drastically reducing SUV sales (which today represent about 40% of car sales).

- In the next 10 years: reducing CO2 emissions by one third, and then half it every further decade. To enable such reduction, we critically need greater system flexibility through digitisation, sector coupling and power-2-X in order to facilitate the integration of new renewables at a scale beyond hydro or nuclear, possibly exceeding 40% in the electricity mix. And we need a solution to drastically reduce emissions from the 2000 GW of installed coal power capacity.

- In the next 20 years: First, managing peak demand without financial collapse and conflict. Second, doubling of electricity supply. And, third, blending at least 5% of synthetic green molecules into existing supply chains, by delivering on about 50 policy measures formulated in 2019 and expanding on early pilots by a multitude of companies. This will be critically important to solve the hard-to-abate sectors.

- By mid-century: Delivering on ambitious yet essential visions such as Net Zero Carbon, Climate Neutral or Road to Zero (carbon emissions) as committed to by almost 70 countries at the recent UN Climate Action Summit or, corporates including many of the members of REN100.

100 years ago, the time was marked by daunting challenges as well as promising new opportunities. The World Energy Council’s founder Daniel Dunlop stood up and imagined, inspired and instituted the necessary change.

100 years later we face arguably humanity’s greatest ever challenge and we are also at the verge of breath-taking and potentially disruptive new opportunities. The task is daunting and complex. It is time now for us all to write history on the foundation of clear-sight, creativity and courage – and deliver the change we need.

Dr. Christoph W. Frei, recent past SecGen & CEO, World Energy Council / chwfrei@gmail.com